Order The Book

E-Book

Audio Book

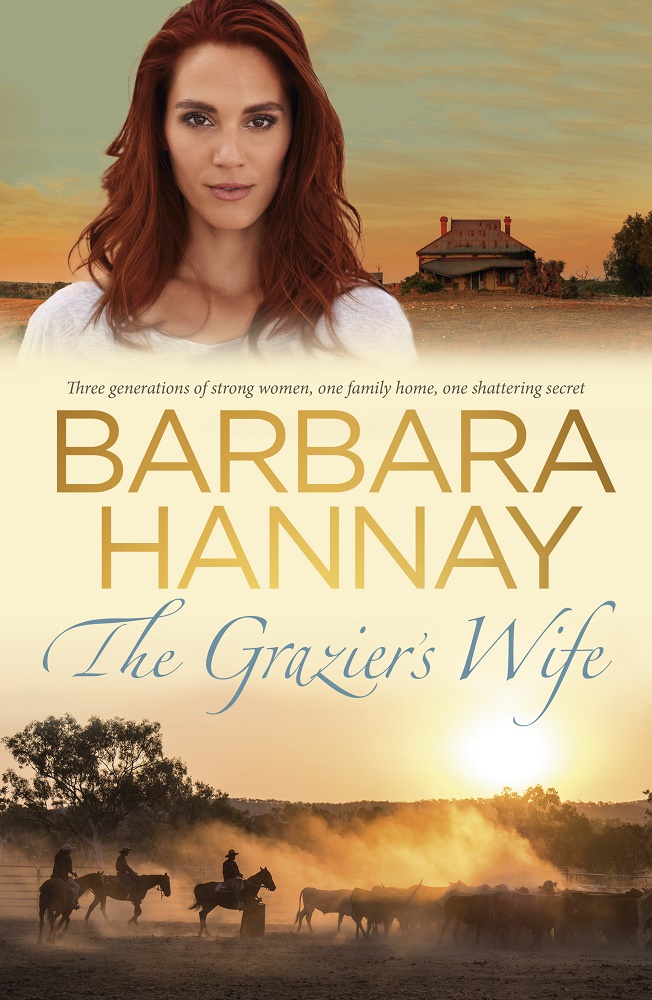

The Grazier's Wife

Three strong women, one shattering secret and a family with the courage to change…

For three generations of Australian women, becoming a grazier’s wife has meant very different things.

For Stella in 1946, it was a compromise after a terrible war.

For Jackie in the 1970s, it was a Cinderella fairytale with an outback prince.

While for Alice in 2015, it is the promise of a bright new future.

Decades earlier, Stella was desperate to right a huge injustice, but now a long held secret threatens to tear the Drummond family of Ruthven Downs apart. On the eve of a special birthday celebration, with half the district invited, the past and the present collide, passions are unleashed and the shocking truth comes spilling out.

From glamorous pre-war Singapore to a vast cattle propert in Queensland’s far north, this sweeping, emotional saga tests the beliefs and hopes of these women as they learn to hold on to loved ones and when to let go.

Apple Books Review

The master of unpretentious Australian romance does it again. The Grazier’s Wife captures all the sights, sounds, smells and, of course, the burning emotions of outback Australia. Barbara Hannay turns her expert story telling to three generations of women on the Queensland cattle property of Ruthven Downs. Coming of age in starkly different eras, Stella, Jackie and Alice each marry into the Drummond clan and then fight to hold the family together. With an ambitious yet tender sweep, Hannay maps out the long, twisting history of a single homestead against the backdrop of a rapidly changing world.

Ruthven Downs, 2014

It had been a long day in the stockyards. As Seth Drummond drove his ute back down the winding, dusty track to the homestead, his thoughts were focused on creature comforts. A hot shower, a fried steak with onions, and a beer. Not necessarily in that order.

Rounding the last bend, he dipped his Akubra against the setting sun and saw the familiar spread of the home paddocks and the horse yards, their timber fences weathered to silvery grey. Beyond the low, sprawling, iron-roofed homestead with its deep verandahs and hanging baskets of ferns, a huge old poinciana tree shaded the house from the western sun.

At the perimeter of the paddocks, a meandering line of paperbarks marked the course of the creek, and as the setting sun’s rays lengthened, the distant hills became folds of rumpled velvet beneath an arching sky that deepened from pale blue to mauve.

Seth had lived here all his life, but he never tired of this view, especially at the end of the day when the landscape was dappled with shadows and light.

Today, however, a strange car was parked near the homestead’s front steps. The small, bright purple sedan looked out of place in this dusty rural setting.

Visitors.

On the passenger’s seat at Seth’s side, the blue cattle dog pricked up his ears and stiffened.

‘Yeah, know how you feel, Ralph.’ Seth gave the dog’s neck a sympathetic scratch. ‘I’m beat. Not in the mood for visitors.’

He edged the ute forward and as he did so, a figure rose from a squatter’s chair on the verandah. A girl in slim blue jeans and a white T-shirt. She had a mane of thick, pale tawny hair, dead straight to her shoulders.

Recognising her, Seth let out a low whistle.

Joanna Dixon, the English backpacker, had scored a job as camp cook on last year’s muster. She’d cooked a mean curry in the camp oven and she’d coped well on the job, giving as good as she got when the ringers labelled her the Pommy jillaroo and teased her about her toffy English accent.

Pretty in a slim, tomboyish way, with surprisingly cool, blue eyes, Joanna had flirted with Seth rather blatantly. But his job had been to lead the mustering team, not to be sidetracked by the chance of a roll in the swag with the hired help.

He had no idea what Joanna was doing back here now, but his recollections were suddenly cut off. Joanna was bending down to lift something from a basket on the verandah.

A small bundle. A baby.

Seth cast a quick glance around the homestead and lawns, but there was no sign of another woman. Joanna was holding the baby against her shoulder now, patting it with a practised air.

Fine hairs lifted on the back of Seth’s neck. He went cold all over. No, surely not.

After the muster last year, Joanna had moved away from the district to pick bananas at a farm near Tully. Seth hadn’t expected to see her again, and he’d been surprised when she’d turned up at the Mareeba Rodeo a couple of weeks later, all smiles and long legs in skinny white jeans. She’d greeted him like a long-lost friend and had mingled easily with his circle of friends.

They’d enjoyed a few laughs, a few drinks. Later that night, primed with rum and Cokes, Joanna had knocked on his motel door. He hadn’t turned her away that time.

Yanking a sharp rein on his galloping thoughts, Seth parked the ute next to her car. He drew several deep breaths and took his time killing the motor. There had to be a sensible explanation for this, an explanation that did not involve him.

Determined to show no sign of panic, he got out of the vehicle slowly. ‘Stay here,’ he told Ralph as the dog slipped out behind him. Obedient as ever, the blue heeler sat in the red dust by the ute’s front wheel, his eyes and ears alert.

The girl on the verandah settled the baby in her arms. Seth removed his Akubra and ran a hand through his hair. After an afternoon in the stockyards, he was dusty and grimy: he’d been branding, ear-tagging and vaccinating a new mob of weaners, fresh from the Mareeba sales. He left his hat on the bonnet as he strolled towards the three low steps that led to the verandah.

‘Hi, Joanna.’

‘Hello, Seth.’

‘Long time no see.’

‘Yes.’ She looked nervous, which was not a good sign. The girl Seth remembered had been brash and overconfident.

‘How long have you been waiting here?’ he asked.

‘Oh.’ She gave a shy shrug. ‘An hour or so.’

‘That’s quite a wait. Sorry there was no one to meet you. I’m afraid I’m the only one home at the moment.’ He forced a smile but it only reached half-mast. ‘I thought you’d be back in England by now.’

‘I’ll be flying home quite soon.’

Relief swept through Seth. He’d been stupidly worrying about nothing. This wasn’t what he’d feared. Joanna was leaving, going back to England.

‘That’s why I needed to see you.’ Joanna dropped her gaze to the baby in her arms, then looked at Seth again. He could see now that her eyes were too big and too wide, displaying an emotion very close to fear.

Alarmed, Seth swallowed. His mind was racing again, trying to recall important details from that night over a year ago. Hadn’t Joanna said she was on the pill?

He found himself staring at the baby, searching for clues, but it just looked cute and tiny like any other baby. Its hair was downy and golden as a duckling, and it had pink cheeks and round blue eyes. It was wearing a grey and red striped jumpsuit and he couldn’t even tell if it was a boy or a girl.

He swallowed again. ‘How can I help you, Joanna?’

Her mouth twisted, and she looked apologetic. So not a good sign. ‘I’ve come to introduce you to Charlie.’

Whack.

‘A – a boy?’

‘Yes.’

Seth couldn’t think. He was too busy panicking. ‘Is – is he yours?’ A stupid question, no doubt, but it was the best he could manage.

‘Yes.’ Joanna gave her lower lip a quick nervous chew. ‘And he’s yours too, Seth.’

Slam. It was like being thrown from a horse and finding himself on the ground, winded. Seth struggled to breathe. ‘I don’t understand.’

‘I’m sorry.’

Joanna truly looked sorry. Unfortunately for Seth, this only compounded the situation. She’d always been so cool and self-assured, and now, as he saw tears glittering in her eyes, an incredible impossibility seemed scarily believable and – damn it – feasible.

‘Didn’t you . . . Weren’t you on the pill?’

‘Yes, but I’d started the pill mid-cycle and things hadn’t settled down. Obviously, I should have been been more careful. I should have warned you, but I never dreamed . . . It was an accident, of course.’

Again she looked down at the baby lying in her arms. She touched his soft hair. ‘I nearly didn’t go through with it. I was so close to having an abortion. I had it all booked and everything. But I – I knew he was yours.’

She looked up at Seth with a sad smile. ‘At the last minute I knew I had to keep him, Seth. I realised I had this little person inside me and I knew that one day he could inherit all this.’ She gave a nod towards the wide, bronzed stretch of the Ruthven Downs paddocks.

Seth could only stare at her. He had no words. He was numb, dumbstruck. Trying to take in the horrifying news.

‘Charlie’s three months old. You can have a DNA test, if you like, but I swear you’re the only guy I slept with around then.’ Lifting her chin, she eyed him steadily. ‘You’re his father, Seth. Your name is on his birth certificate. He’s Charles Drummond.’

Seth still couldn’t think straight, but he forced his legs to move, to mount the steps. ‘You’d better come inside.’

‘Right, thanks.’ With surprising speed, Joanna scooped up a bulging zipper bag and the basket, which Seth now realised was actually one of those capsules for putting babies into cars.

It was a lot to juggle when she had the baby as well. He wasn’t keen to help her. It would be like admitting to a truth he didn’t want to accept, but the good manners ingrained in him from birth were too strong. He held out his hand. ‘I’ll take those.’

‘Thank you.’

The homestead door wasn’t locked. Propping it ajar with one elbow, Seth nodded for Joanna to precede him into the central hallway. ‘Lounge room’s on the right,’ he said, knowing she’d never been in the house before. When she’d been on Ruthven Downs previously, she’d only ever slept in the ringers’ quarters or in a swag under the stars.

Now he followed her into the lounge room, still furnished with the same old-fashioned chintz and silky-oak sofas and armchairs that had been in the house since his grandparents’ day. The long room was divided by a timber archway and at the far end was the dining area, dominated by a rather grand, mirror-backed sideboard where a collection of photos depicted the history of Seth’s family. The Drummonds of Ruthven Downs.

Seth’s great-grandfather Hamish Drummond was there in faded sepia, looking serious and heroic in his World War I army uniform. In another frame, Seth’s grandparents stood together on their wedding day, his grandfather Magnus looking ever so slightly smug. Then his father, Hugh, as a baby in a long, white christening robe. His parents, rugged up in thick coats and scarves, on their honeymoon in the Blue Mountains. Seth was there too, aged around ten. He and his sister were both on horseback. There were even photos of his aunt and cousin.

Now, as Seth set the baby capsule and bag in a corner next to a faded gold and cream oriental rug, he felt as if the four generations of family photographs were somehow watching him. Reproaching him for fathering a bastard.

‘Take a seat, Joanna.’

‘Thank you.’ She seemed as edgy as he was and she sat with a very straight back.

‘Would you like a drink? Water? A cuppa?’

‘I’m fine, thanks. I have a water bottle. I can’t stay long.’

Seth frowned. He supposed he should be relieved that this was only a brief call. She was going back to England, so at least she wasn’t planning to move in with him.

But there were so many questions. He was too tense to sit. ‘How come this has taken so long?’ He tried not to glare at her, but he had no hope of smiling. ‘You’ve known about – about him for a year. Why suddenly decide to turn up now out of the blue?’

The baby gave a little mewing cry and she settled him against her shoulder and began to pat his back again. She drew a deep breath. ‘Look, I know I haven’t handled this well. For ages I tried to carry on as if the pregnancy wasn’t really happening.’

After only the briefest pause, she hurried on with her story. ‘I had a job on a property just outside of Broome, doing a little cooking and helping the kids with School of the Air. I often thought about getting in touch with you, coming to see you, but I – I was worried. I was worried about your family’s reaction.’

Giving a sheepish half-smile, she quickly dropped her gaze. ‘Then I saw on Facebook that your parents were away on holiday in Spain . . .’

A nasty chill streaked down Seth’s spine. Joanna was spying on his family? He felt instantly defensive about his parents, who were away on their first overseas holiday, a long-overdue luxury that they both deserved so much.

‘You mentioned that you’ll be leaving for England soon.’

‘Yes.’

‘And you’re taking Charlie.’

‘No, Seth.’

Seth had been standing, but now, blindsided, his knees caved and he sank swiftly into the armchair opposite her. The truth was suddenly, painfully obvious. Joanna was dumping the kid on him. That was why she’d come. Now, while the baby’s grandparents were safely out of the country. She didn’t have the guts to face them as well.

‘I’m getting married, you see,’ she said matter-of-factly. With her chin high and sounding more like the calm and ‘together’ girl that Seth remembered, Joanna added, ‘It’s been planned for ages. My fiancé is Nigel Fox-Richards.’

After an expectant pause during which Seth made no response, she continued less certainly, ‘We didn’t have a formal engagement, but it was all settled before I left England. Nigel’s family has an estate in Northumberland. They’re – they’re quite well off.’

‘How jolly,’ Seth responded bitterly.

She had the grace to blush.

‘So how does that work?’ Distaste lent a hard edge to his voice, but he was too angry to care. ‘Were you allowed your little adventure in the colonies before you settled down to married life in the castle?’

‘Well, I suppose it was more or less like that. Nigel had this list of adventures, you see – trekking the Himalayas, sailing to the West Indies, hugging polar bears or whatever. He wanted to tick them off before he got too busy with the estate and our life together, so we agreed on eighteen months apart. Now Nigel’s father’s health is failing and it’s time to take on all sorts of responsibilities.’

Bizarrely, Seth could already picture Joanna fitting into that scene. She certainly had the posh accent and he could imagine her in skin-tight cream jodhpurs and knee-high boots, a riding crop tucked under one arm, a string of pearls around her tanned throat.

‘How does Nigel feel about Charlie?’

‘He doesn’t know about Charlie.’ Her mouth tightened and her eyes were suddenly hard and determined. ‘He’s not going to know about him. He can’t. He mustn’t. That’s the thing, you see.’

‘No, I don’t see.’ Seth was on his feet again now, too angry to sit. ‘You’d better explain. Preferably in words of one syllable, so everything’s perfectly clear.’

Joanna sat even straighter, shoulders squared. ‘I can’t take Charlie back to England, Seth. There’s no way that Nigel’s family would accept him.’

So, at last, the truth. Joanna was going to marry her Lord Fauntleroy, and she needed to keep her Aussie bastard hidden.

Seth’s anger spilled. ‘For fuck’s sake, Joanna, how the hell can you be so bloody casual about this?’ Dramatically, he threw his arms wide. ‘Oops, I’ve had a baby, and here he is, and now I’m off home to England.’ He shot her his fiercest glare. ‘Is that the best you can bloody do?’

He should have known she would give as good as she got.

‘Don’t forget, Seth,’ she said coolly, ‘you were as keen as I was at the time. And you were also pretty bloody casual about our relationship. When I left, I got a kiss on the cheek and a pat on the bum. Goodbye and happy memories of my trip Down Under.’

‘Well, yeah,’ Seth said defensively. ‘But if I’d known this had happened, I would have –’ He hesitated, unsure of his ground. ‘I suppose I knew you would have done your best to help me, to look after me and Charlie. I never really doubted that. The problem was –’

Now it was Joanna’s turn to hesitate.

‘You didn’t want my help,’ Seth supplied. ‘It would have complicated your life. I might have tried to ruin your plans.’

‘Yes.’ For a moment she almost looked penitent, but then she said calmly, ‘Now it’s your call, Seth. You asked me to make everything clear. And I’m asking you now – do you want Charlie, or not?’

No. Hell, no.

I can’t possibly . . .

It was way too sudden. Most guys had nine months to get used to this sort of news . . .

For the first time, Seth looked properly at the striped bundle in Joanna’s arms. The baby was curled up like a koala – his golden head lying against her shoulder and one small, dimpled hand resting on her breast. He had fat cheeks and neat little ears. His eyelashes were blond and his eyelids heavy, drooping sleepily.

This was Seth’s son. His flesh and blood.

His son. If Joanna was telling the truth – and Seth suspected she was – this tiny scrap of humanity carried Drummond genes. He was Charlie Drummond. He was going to grow into a toddler, a schoolboy, a teenager.

A man.

I knew that one day he could inherit all this.

Emotion clawed at Seth’s throat. Anger again, certainly. He was furious with Joanna for her secrecy, for treating him like a last resort. He felt fear, too, as he contemplated the responsibility suddenly landed on him. His lifestyle, his freedom – hell, his whole life as he knew it – would be totally stuffed.

And then, very much to his surprise, Seth felt another emotion emerging, something deep and primal and unexpected: a fierce welling up of protectiveness.

But hell.

‘Are you expecting us – me – to take care of Charlie?’

Joanna nodded. ‘That would be the ideal situation.’

‘What if I told you that I couldn’t?’

She drew a deep breath. ‘I know this must be a terrible shock, Seth, and I apologise for landing it on you like this, but the only alternative I can think of is to hand him over to the state for adoption.’

Adoption? A ward of the state?

Seth was surprised by the vehemence of his reaction.

Heaven knew he didn’t want a baby. He had a cattle station to run and while he knew a fair bit about caring for newborn calves, he knew absolutely zilch about looking after a human baby. More importantly, he thoroughly enjoyed being a bachelor.

Joanna’s bombshell was as shocking and unwelcome as a grim health diagnosis for a person who’d always been fit and well. And yet . . . Seth knew that life could deal hefty punches from time to time. If he was honest, he’d had a pretty free run so far. He’d grown up in a beautiful part of the country, had enjoyed the fun of boarding school, representative rugby union, university. The life of a cattleman, the life that he’d always wanted, had been handed to him on a plate.

Joanna was right. When they’d had their careless, casual fling, he’d been a very willing partner. Now, he had little choice but to cop this blow. An unpleasant reality had to be faced and, to his own somewhat stupefied amazement, he was already coming to terms with this new and weighty responsibility. Charlie.

But there were still questions to be asked.

In a desperate bid to get his head straight, Seth marched to the French doors that looked out across the dusk-shadowed landscape. He saw the fiery glow on the rim of the distant hills. The evening star was already showing and he watched the flight of a trio of ibises, their long necks straining as they winged their way homewards.

He turned. ‘Are you sure you’ve thought this through? Can you really give up your baby? He looks well cared for. I’d say you’ve been a good mother. How are you going to feel down the track, Joanna? Have you thought about that?’

‘Of course.’

‘Say he settles in here, becomes part of this family. How do I know you won’t turn up in a few years’ time to tell me you’ve changed your mind?’

‘That won’t happen, Seth.’

He might have rejected this assertion if he hadn’t seen the silver glitter of tears in Joanna’s eyes. Her mask had slipped and the pain and stoic resolution in her face told their own story. She had made a difficult choice and now she was determined to go through with it. All the way.

‘Well,’ Seth said quietly, as he eyed the bulging zippered bag, which presumably contained all the necessary equipment for the baby’s care. ‘I suppose you’d better show me what’s involved in feeding him.’ She smiled shakily as he returned from the French doors. ‘Here,’ she said. ‘You should at least hold him.’

Seth drew a sharp breath, then held out his arms, stiffly bent at the elbows.

‘You can relax a bit. You just need to support his head,’ Joanna said. ‘His neck’s not very strong yet.’

The little guy was now in Seth’s arms. So small and warm. He felt his throat tighten.

‘Is the name okay?’ Joanna’s eyes were too bright. ‘I thought about asking you first, but I was too scared. I wanted to tell you about him, you know, face to face.’

Seth shrugged. ‘Charlie, Charles, Chas – anything, as long as he’s not called Chuck.’

For the first time, they both smiled. In his arms, the baby wriggled. ‘Hey, Charlie.’ Seth’s voice was choked.

Charlie looked up at him, frowning like an old man with all the worries of the world, but staring solemnly, straight into Seth’s eyes.

‘G’day, little mate,’ Seth said, and he was rewarded with a heartbreaking, toothless grin.