– THE COLT WITH NO REGRETS – by Elliot Hannay

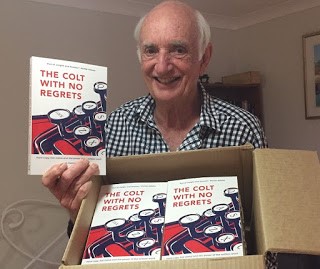

There was great excitement in our household this week as the first copies of my husband’s memoir arrived from Wilkinson Publishers.

Welcomed by Phillip Adams as an important Australian memoir full of insight and humour, this is also a story about growing up.

It’s the personal journey of a 16-year-old boy starting work in “the golden age of journalism” when reporters toiled with hard copy and hot metal and endured a mixture of instruction and reprimand that would be branded today as workplace harassment.

Follow a boy gripped with an intense fear of failure in the first weeks of his probation, to the height of his career as a hardened and experienced newspaper editor confronting the Ku Klux Klan, being threatened by dangerously corrupt police, and breaking international news from the inner sanctum of the Chinese Communist Party.

Lessons from the past in a sparkling narrative which has been endorsed across the political spectrum.

The Colt (aged 16) reporting on rainfall, temperatures, tide times and baby shows. Righting wrongs and exposing injustice will have to wait.

The Colt (aged 38) facing the downside of righting wrongs and exposing injustice… death threats and a $3 million writ from Kings Cross underworld figure Abe Saffron.

By a strange quirk of fate, this story is arriving in the same week as the announcement that small regional newspapers, including the Bundaberg News Mail where Elliot first started work, are no longer going to be printed. Elliot and I are both saddened by this.

These papers were important sources of connection and pride for local communities. They also gave their communities a morale boost and kept local councils on their toes. However, I’m also very proud that my husband’s record of a bygone era has been published.

“Let his musings remind us of what we are losing

before it is entirely lost.”

Phillip Adams

And if you’d like a taste, here’s an extract…

“The Colt With No Regrets”

Prologue

A double brandy on a double brandy

Myles Harrington Carruthers stepped off a slow train from Brisbane with no luggage and wandered into The Imperial an hour before closing.

I wasn’t anywhere near legal drinking age, but I was there when it happened. But it was okay. I was into my second year working at the paper next door, and I had been given the nod.

I had been taken in one day by Tommy and Mervyn and received the nod from Mother Moore, the widow publican.

“Always wear a coat and tie when you’re with us, Colt. Stand up straight so you look older than you are, make sure you start with a dash of sarsaparilla in the first beer and stay off the rum until you’re twenty-one… and for God’s sake loosen that tie, pull the knot over to one side so you look like you’re taking a well-earned break and not about to attend a bloody funeral.”

My entry to this world of men also got the nod from the plain-clothes who never seemed to pay for their drinks. Detective Sergeant Neil Harvey looked like a grey goshawk watching a duckling in a chook pen on the first day I walked into the bar.

He looked at Mother Moore who gave him the nod, then turned to Tommy and Mervyn and they all exchanged nods. He ignored me. I badly wanted to give someone the nod.

By the time Myles Carruthers hit town, I thought I was a competent nodder, but modified my modus operandi after Tommy pulled me up short. “Stop it, Colt, you’re nodding to every poor bastard who walks through the door. You look like a bloody parrot in a cage.”

So, I didn’t nod at Myles Carruthers when he stepped through The Imperial’s old batwing doors, letting a chilly westerly sweep through the bar.

He was pale, pink and skinny and he looked crook. I was young, and he seemed old. He had a nylon Hawaiian print shirt stuck into light brown corduroy shorts that were soiled around the pockets. Dirty white short socks and what looked like plastic slippers.

Myles was dressed like an English remittance man in sultry Singapore, but it was a cold Bundaberg winter’s night. Later, his fellow drinkers would suggest that he’d consumed so much alcohol that his blood chemistry had changed, and it acted as an effective anti-freeze.

In the four years he was with us, I never saw him wear a jacket and can only recall the shirts changing. The corduroy shorts, unwashed socks and plastic shoes, took on the appearance of permanent attire.

His arrival in the pub that night became the stuff of legends in later years. I vividly remember him ordering a double brandy on a double brandy in a plummy, almost stuttering English accent that silenced the noisy bar.

That’s when I first saw his trademark pub theatre. The glass raised high into the air for inspection against the hard-overhead lights, like an Amsterdam diamond cutter appraising the largest stone he’d ever seen. The other hand, with the little finger sticking up in the air, sweeping back his long greyish- blonde hair.

Then, just as you were preparing for the bar to erupt with derision, Myles, with the timing of a Shakespearean actor, would put glass to mouth and with a sudden tilt of his head backwards, drain four shots of Chateau Tanunda brandy in a split second.

We all realised in that first hour of his first night with us, that Myles was in the grip of the grog. He could repeat the quadruple brandy theatre until he ran out of cash or credit.

Like the worst of alcoholics, Myles had a huge capacity for drink and it soon became obvious that beer, even Aussie beer, was but well water to the demon inside him.

He told me much later that he was greatly relieved that first night when he saw soot- blackened cane cutters drinking beer with five-ounce over-proof rum chasers. They were so black from working in the burnt sugarcane that Myles first thought they must have been coal miners, but it was their capacity to quaff strong spirit that really impressed him.

“A civilised society cannot be maintained by beer alone, old boy. Spirit drinkers are a sign of civilisation. Distilling is a gift from God, passed to us through the ancient monks. It is all about the search for purity and essence, just like a good tabloid sub being able to condense four hundred words of purple prose into a beautiful intro, supported by two meaningful and informative paragraphs.”

Yes, Myles was one of us, a newspaperman, and a hard copy journo.

Others in town came to describe him as a con man, a bullshit artist, a queer and a bad influence, but I believe he was the closest I ever came to having a real English gentleman as a friend.

You can order this book from the following stores:

Amazon Aust

Booktopia

QBD Books

Angus and Robertson

Wilkinson Publishing

Dymocks

Hi Barbara. I just finished the Colt With No Regrets. I am not a journalist, but I have a long list of country town experiences in Queensland, often intersecting with Elliot (although he is a bit older). The book is so clean, full of life. Emotive.

The only thing missing is “what happened to Myles?”. Such a focal point, but no epilogue. If it possible to share the answer to that? No real reason, and I am not gay. I guess its just that Myles reminds me of some people I know.

I did leave Elliot a message on messenger, but perhaps he does not look at it.

Hope you are both keeping well.

David French

Rockhampton